Sources are important in different writings that we encounter on a daily basis. They are most commonly used when writing papers, assignments, and in other forms. Moreover, sources are important when presenting written research in different fields, including history, sciences, and arts. They help in giving the reader assurance that the writing was either obtained from the writer’s own reasoning or from the research of other people. At some point in college, bystanders may have witnessed students getting in trouble for plagiarism. Failure to cite sources results in plagiarism and this brings about hefty penalties. Different institutions and universities have made it mandatory to cite sources depending on whether the student obtained information from different sources or from his or her own reasoning.

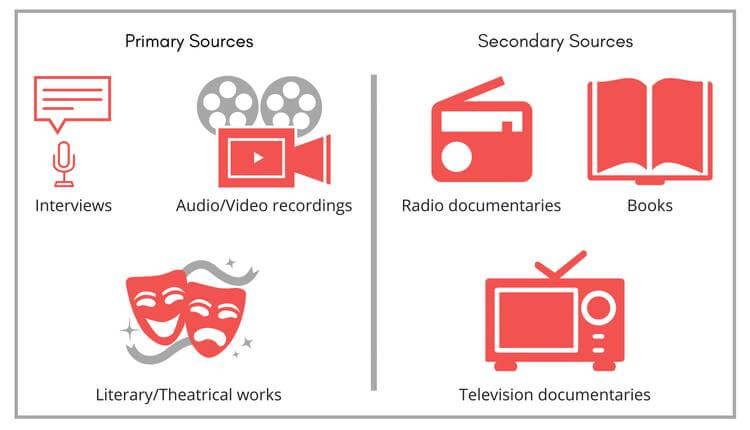

Sources are either primary or secondary. The table below shows some of the differences between both the types of sources.

| Primary Sources

|

Secondary Sources

|

| These are original documents. For example, diaries, artwork, poems, letters, journals, treaties, and speeches fall under primary sources. | Secondary sources interpret primary sources. For example, they can be articles, television documentaries, conferences, biographies, essays, and critiques of a piece of art. |

| They are written by people with experience. Professors in specific fields may write these. | They are written by people or writers seeking information or conducting research such as students. |

Deciding Between Primary and Secondary Sources

It may be difficult to identify a primary and a secondary source. This is often experienced by most individuals, especially while composing research papers, assignments, or journal articles. Finding just the right source is the most important factor when citing information from different sources. So how can a writer determine which source is the best for a particular project? Distinguishing between secondary and primary sources should not be a problem to the reader after going through the following points.

Primary sources are written by specific individuals who said or wrote about a theory or event. Secondary sources are often pieces of writing that elaborate on the original source. Primary research comprises of original research about various crucial topics. However, for secondary sources, the information obtained from primary sources form the baseline of the content.

Primary sources comprise of data obtained from surveys, census, economic statistics, or different datasets that have not been recorded before. Secondary sources also contain such data and are referenced to the original primary sources.

Secondary sources are mostly scholarly in nature. A source is considered scholarly when the authors were not directly involved in gathering the original information. Secondary sources contain information from different primary sources, all in one piece. In addition, it is important to consider the credibility of the sources before citing them. This helps the writer avoid the inclusion of false information in articles, research papers, journals, or writing assignments.

Citing Secondary Sources and Citation References

Some of the more popular secondary sources include MLA, APA, and Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS). These are basically citation styles that enable the writers to cite information obtained from different sources. In APA style, the reference list comprises the sources that the writer read in particular. The page number, author, and date of the source are required. In-text citations are included in parenthesis. Moreover, the author should be acknowledged in the sentences. In MLA style, the writer should reference the source. In CMOS, there are only two formats, the author-date, and note.

You can now distinguish between primary and secondary sources. You can also comfortably use any of the above citation styles. So how will you use primary sources in your writings?