Manuscripts provide novel insights that reflect the authenticity and originality of the work when writing and sharing data. To combat plagiarism in manuscripts, CrossCheck (now Similarity Check) has been increasingly used to prevent plagiarism, or reduce the number of duplicate submissions. Similarity Check, powered by iThenticate, evolved as a collaboration between major publishers and CrossRef. It allows editors, publishers, authors, and readers to check submitted articles against a database of millions of other academic journals. This tool allows people to detect plagiarism using an automated text similarity checker.

Features of Similarity Check

After an article is uploaded, Similarity Check scans the manuscript for similarities to previously published content. It compares full-text manuscripts against more than 38 million articles and more than 20 billion web pages. You can check here if your journal uploads its information.

Of course, some writing will be very similar to various other articles. Hence, results are reviewed to determine the nature of the duplicated text. Nevertheless, several organizations use this software, including Springer, BiomedCentral, Adis, Birkhauser, and Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. Meanwhile, other organizations, like the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), require all papers for proceedings and conferences be screened via a plagiarism detection process.

Volunteers or staff of various organizations then review the reports generated by Similarity Check to determine the nature of the similarity and if any action is warranted.

A Quick User’s Guide

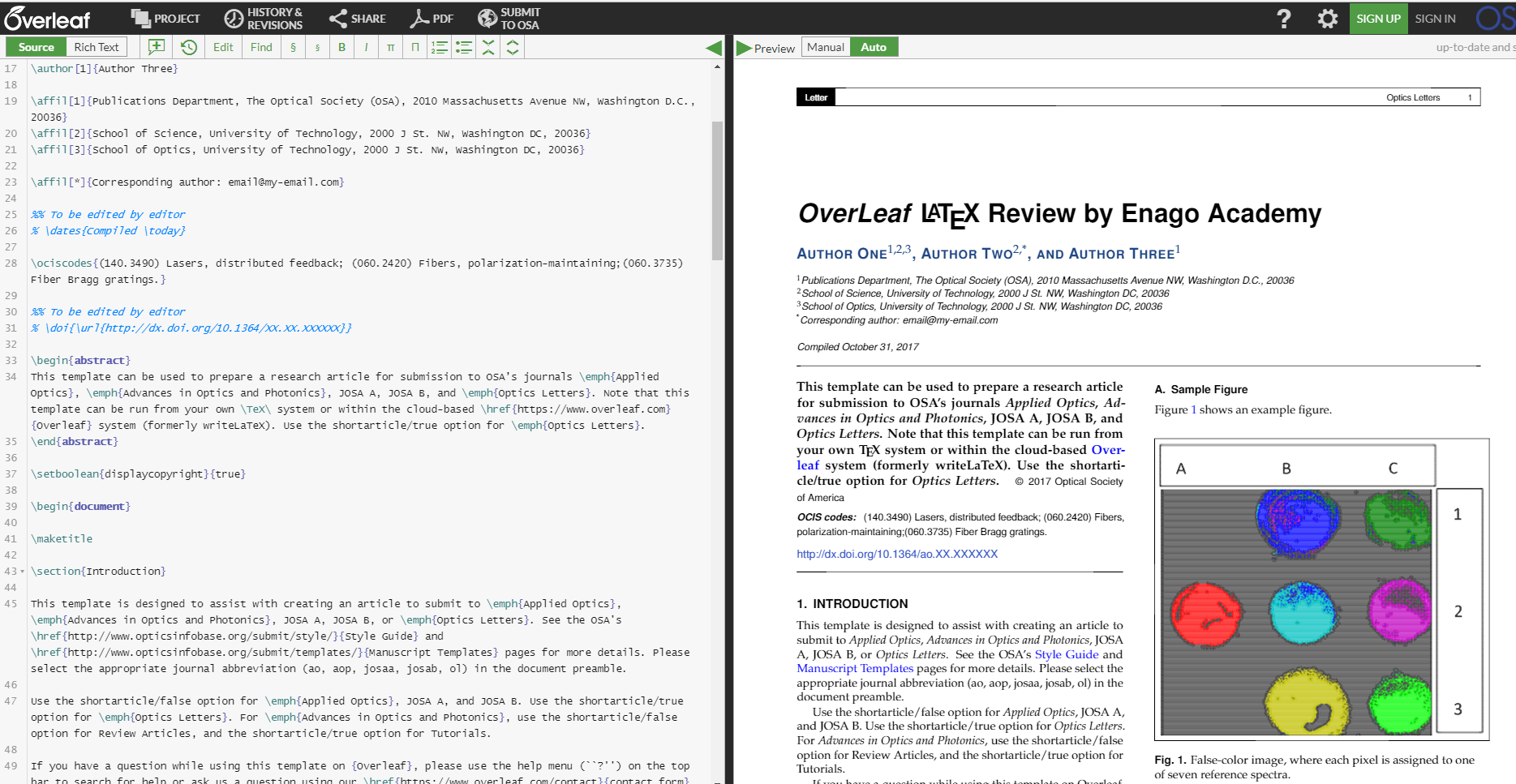

Staff members of various publishing organizations and publications volunteers (e.g., authors, editors, etc.) upload new manuscripts into the database. This can either be done manually or might require some help from the publications volunteer.

When a publication reaches a threshold, such as 30% (as recommended by the IEEE), the person who has uploaded the manuscript is notified electronically. This threshold can be modified to any amount and is linked to an email alert system.

The submission is then reviewed. A report is generated that highlights similarities, which must be carefully reviewed to discern actual plagiarism from coincidental writing. The report shows the combined or total score of individual similarities. These reports can be modified based on similarity, content tracking, or largest matches.

Similarity Check for Authors from Aries Systems Corporation on Vimeo.

Similarity Check for Editors from Aries Systems Corporation on Vimeo.

What Your Results Mean

The similarity reports have several features:

Text is highlighted in a color and indicated by a number

The original source is then indicated on a side panel and is colored and numbered to match the in-text coding

The percentage of similarity of the article to an individual source is indicated for each article or source that shares common language

The summation of individual article similarity scores is presented

An individual must review this report and consider several variables, such as the extent of the similarity, the originality of the copied material (e.g., standard or routine language), the context of the similar material, and the attribution to author or source. When considering the individual similarity scores of each source, Springer recommends that a score of 1-5% requires no checking, >10% requires quick checking, and >20% requires thorough checking.

Important Considerations

Given the nature of publishing and academic writing, duplicated text might become unnecessarily flagged for several reasons. These can include when updating a systematic review, mentioning contributions of an author, self-citation, or “patch writing” that involves several small segments of routine language

In some instances, cultures vary on the nature of plagiarism. Some communities may believe that copying is a sign of respect while others value individuality or uniqueness. Furthermore, senior authors may not have been aware of a junior author’s missteps. Alternatively, authors may have granted permission to duplicate or reuse the text.

Ultimately, the integrity of a scientist is paramount to ensure that the research work is perceived with trust. Using Similarity Check’s report, an author can review what others are writing and ensure that his or her text does not inadvertently repeat the work of another author. As science progresses and becomes more competitive, the writing of scientists will come under greater scrutiny.