There is a constant rise in the number of articles published in predatory journals. Young, inexperienced researchers are the main target of a growing group of dubious publishers that is willing to accept almost any manuscript (regardless of the quality or authenticity) for a fee. These supposedly academic companies do not offer any services, such as peer review or archiving, and have no problem in publishing low-quality papers if the authors pay for the same. Their websites are usually unstable/poorly designed and the articles they publish are not indexed by Medline or similar databases.

Who Publishes in Predatory Journals?

According to a survey that was carried out at the beginning of the year, researchers working in developing countries (those with insufficient funds, poor research infrastructure, and limited training) are more susceptible to submitting their work to predatory journals. The idea of getting something published quickly can be quite appealing to some researchers, and receiving invitations from journals or having their papers accepted easily can give them a (false) feeling of success.

A recent study published in Nature shows that researchers from wealthy nations also fall prey to predatory publishing. David Moher, an epidemiologist at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute in Ontario, Canada, and several colleagues spent 12 months analyzing almost 2,000 articles from about 200 suspected predatory journals. They found that more than half of the corresponding authors came from high- and upper-middle-income countries and that many articles had been submitted from institutions in the United States. Interestingly, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) was frequently named as one of the funding agencies.

An Urgent Problem

The authors point out that “the problem of predatory journals is more urgent than many realize.” In their study, they also assessed the quality of papers published in those journals and found that most experiments could not be reproduced or evaluated properly because of missing information. Additionally, only 40% of the studies carried out on humans and animals mentioned something about seeking approval from an ethics committee, whereas in regular journals, such approval is reported for more than 90% of the animal and 70% of the human investigations.

Based on their results, Moher and colleagues estimate that at least 18,000 funded biomedical research studies end up in dubious, obscure, and poorly indexed journals. These publications do not advance science at all as they are usually of low quality and are also difficult to locate.

Global Predation

An evaluation of over 1,900 papers published in potentially predatory journals (based on Beall’s list, which was taken offline at the beginning of this year) showed that the corresponding authors of all such publications mainly originated from India (27%), the United States (15%), Nigeria (5%), Iran (4%), and Japan (4%). However, to understand these numbers, it is important to consider the total scientific output per nation (last year, the United States produced about five times more biomedical articles than India and 80 times more than Nigeria).

Stop the Plague!

Kelly Cobey, a publications officer at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute in Canada (and one of the authors of the Nature study), is in charge of educating researchers and guiding them in their journal submission. She also helps them identify and avoid predatory journals. Unfortunately, many research institutions do not have staff members with similar roles, so what else can we do to stop the plague of predatory publishers in academic publishing?

One thing is clear: we must act immediately! To start with, it is important to tell the public what these dubious publishers are doing and warn authors (especially the inexperienced researchers) about the consequences of publishing their work in shady journals. Funding agencies, research institutions, and reputed publishers should work together to issue clear warnings against illegitimate journals and introduce recommendations on publication integrity.

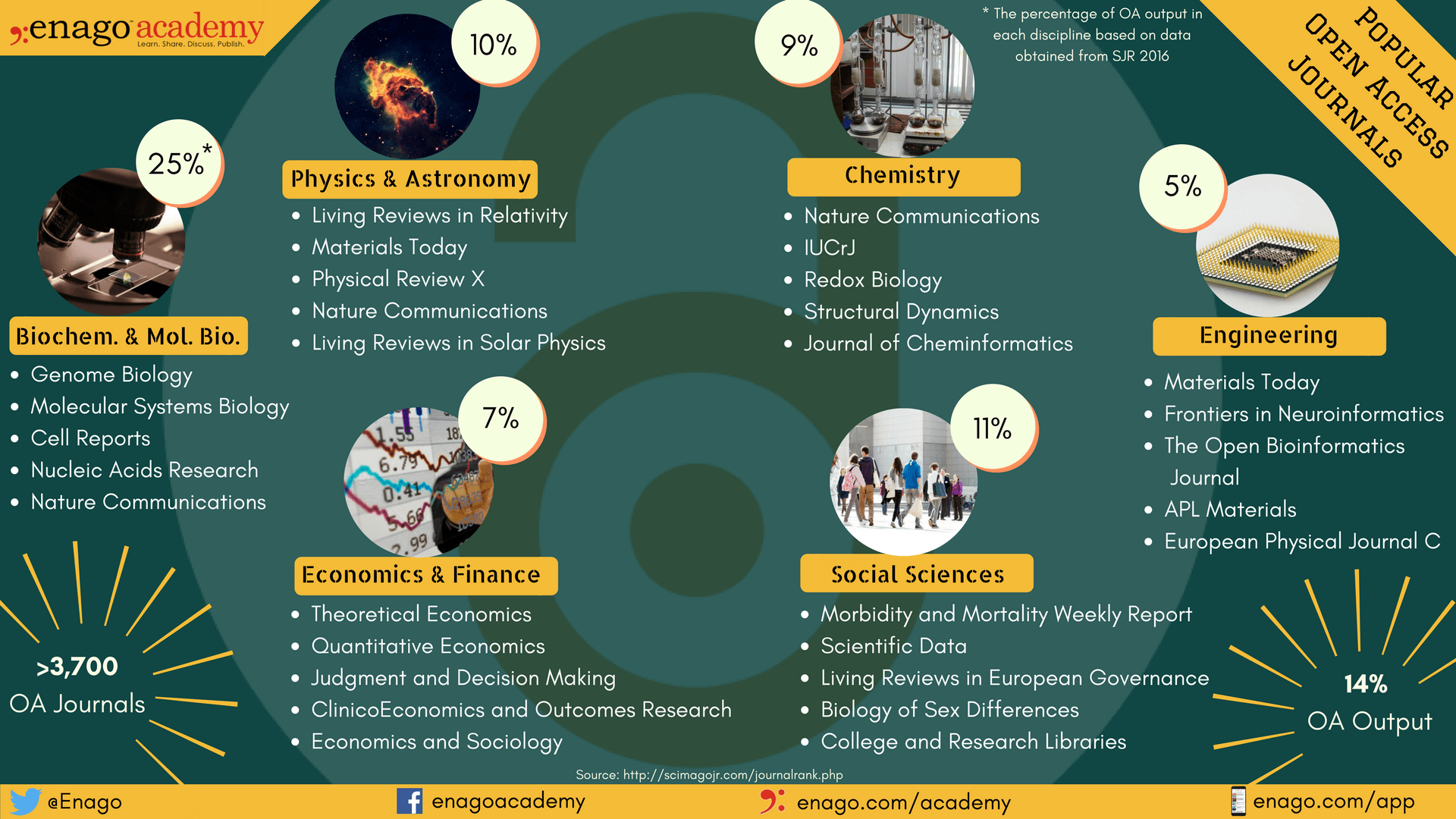

Moher, Cobey, and colleagues also suggest that funders and research institutions should increase the amount of money available for open-access publishing, ensure that researchers are able to identify questionable journals and prohibit the use of funds for submitting papers to predatory journals. They should also monitor where exactly all the grantees and staff members publish their funded work (developing automated tools to achieve this would be immensely valuable).

Manuscripts published in predatory journals should not be considered for granting promotions, appraisals, tenure, or subsequent funding. Moher et al. even suggest that scientists wanting to advance in their careers or looking for research funding should be asked to include a declaration that they have never published in predatory journals (and that they do not intend to do so). Publication lists could then be checked against the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) or the Journal Citation Reports, the researchers say.