There are several tools available to help you plan your research project. They help you organize your thoughts and create a research plan against a timeline. One such tool is called a Gantt chart. Gantt charts were first created in the mid-1890s and revised by Henry Gantt in the early 1900s. Gantt charts are often used in businesses to plan projects and events. They allow managers to stay focused on both monetary and time constraints. Simple Gantt charts list project activities against points in time. More elaborate Gantt charts show more details, such as milestones (discussed below). Time slots/duration would include, for example, the project start date, intermediate time points of importance, and the ending date.

You Need to Plan

Many projects exceed both budgets and timelines. Lack of planning is a major reason for this. Nearly all research projects have some constraints to moving forward. These can be because of delayed funding or availability of an onsite laboratory. Internal structure and political situation might also play a role that could delay a project.

Although planning your project can be a daunting task, a Gantt chart can be of tremendous help. Furthermore, funders will be more willing to discuss your project if you are well organized and prepared. In one of his recent blogs, Jonathan O’Donnell, funding mentor, stated that every application should include a Gantt chart. Proper planning provides assurances that you are well organized. If you are approaching a funder that you have approached in the past, they will consider how organized your previous project was and will base their decision on its success.

Your Research Plan

Your research plan is your guide. It must be carefully thought out and might take several iterations before you are confident about it. Your project’s activity timeline is a very important element of your plan. The duration of each must be logical and realistic. Give yourself enough time for each task. Try never to cut short the timeframe on any important task.

The Gantt chart will help you to stay on track with these activities, which can actually affect the execution and completion of your project. It also provides information on important activities that are defined as “milestones.” For example, say that the time when a particular laboratory is available is a constraint. Any time that a specific activity cannot be performed because of a constraint on laboratory timings should be clearly marked. Every team member must be aware of this constraint.

Another example is that one activity might depend on another. A second activity can begin only when the first activity has reached a specific point. That would be another milestone and should be clearly marked.

Creating Your Gantt Chart

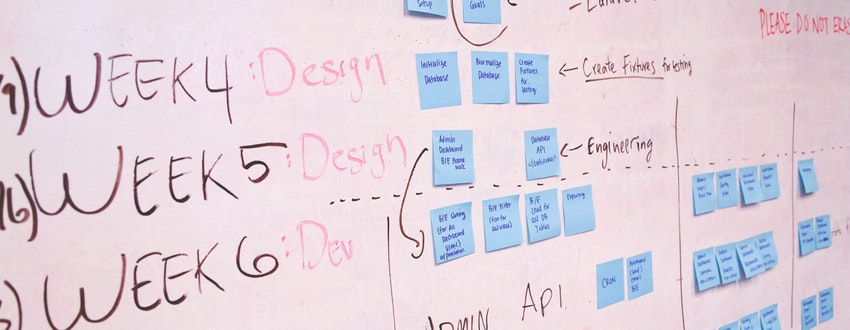

Once you get your thoughts organized, the steps to creating your Gantt chart are fairly simple as follows:

- List step-by-step activities: Make this a very detailed compilation. It will keep you focused and provide information on what resources you need.

- Estimate how long each activity will take: Estimate the duration of each task/activity. Consider possible lag and lead time in all the activities. You can use days, weeks, or hours to make Gantt charts.

- Organize activities logically with constraints and milestones: If possible, eliminate any activity constraint. For example, if your university lab is not available at specific times, consider an alternative, such as renting space.

- Combine activities: Rather than creating an enormous activity list, combine like activities into groups. Combine timeframes into larger chunks. For example, if your project will last 5 years, divide the timeline into quarters instead of listing days or months.

Your completed Gantt chart will now present a project “picture.” This will provide a view “at a glance” of your project to all stakeholders. It will also provide you and your team with a clear set of goals.

Apart from MS Project, you can use various online platforms to create Gantt charts.

Make Changes Carefully

It is easy to make revisions to your Gantt chart, but avoid making changes at random for no valid reason. For example, any delays caused by a team member that could have been prevented is not a valid reason for changing your plan. Random and frequent changes to your plan might send a message that you are not organized.